I’m on a Willie Nelson kick.

These things happen when I read books about an artist. And my book of choice of late is Willie’s Energy Follows Thought, a collection of his lyrics. “The stories behind my songs” says the subtitle.

“Hang on,” I hear you saying. “How deep can the backstory of ‘On The Road Again’ really be?”

I won’t give it away because I think you should absorb the book, but here’s something he says about “On The Road Again” – “Without knowing or trying, in a few little lines I’d written the story of my life.”

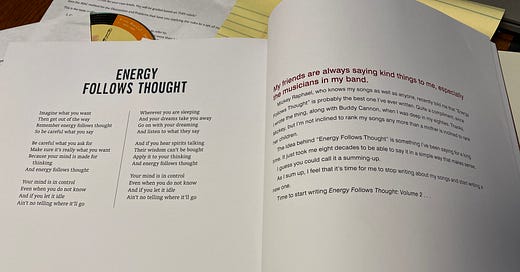

The compendium revealed what should’ve been obvious to me all along: Willie’s songs don’t have a lot of lyrics. “Night Life.” “Once More With Feeling.” “Crazy.” “Hello Walls.” And “Energy Follows Thought,” a masterpiece he wrote at age 89 and that which gives his book its worthy title. It’s economic writing at its finest.

Willie Nelson is like some bizarre hybrid of Shakespeare, Louis Armstrong, and the dusty philosophy instinctive to great songwriters from Texas. Reading through the pages of lyrics and the suitably brief discussions thereon, I’m entirely moved, motivated, and enlightened.

I regret becoming aware of Willie Nelson in his “On The Road Again” heyday. Hearing it on Casey Kasem’s “American Top 40” irritated me; it sounded more like a novelty song than anything serious. Willie, to me, was nothing more than a brand riding the “Urban Cowboy” coattails – a bias drilled into me across the 1980s as Nashville’s money machine churned out album after album of Willie singing just about anything anyone threw at his record company.

It's still hard to keep up with Willie’s deluge of new recordings, but it’s different this time around. Nowadays, Willie pops out albums that mix originals and cover songs deserving of his weathered insight. It’s not for the money. Records don’t sell these days. These are late-in-life artistic surges, each with something to say that goes well beyond record company balance sheets.

That’s not to say Willie’s 21st Century output doesn’t have its share of clunkers, but they come thanks to the shortsighted corporate nabobs who think they can capitalize on Brand Willie by pairing him with flavors of the month like Rob Thomas (that guy from Matchbox 21) and Sheryl Crow (lots of people like her but geez she’s a lightweight) or cashing in on his propensity to roll a doobie. Avoid those. His last half-dozen albums are winners.

Rob Thomas missteps aside, Willie is, of course, among a handful of quintessential interpreters of others who show up with strong voices of their own. Tom Waits (“Picture in a Frame”), Rodney Crowell (“Til I Can Gain Control Again”), Gram Parsons (“$1000 Wedding”).

This is not breaking news: the guy is a treasure.

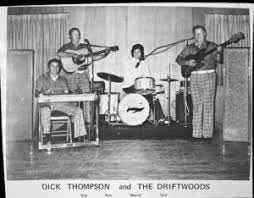

My pal John Thompson drip-fed country records to me in high school and let me sit in with his dad’s band, The Driftwoods, where I’d play a standard shuffle to obscure country songs I’d never heard before but that his dad, the great Dick Thompson, would pull out of his head like a human jukebox. It took a few years for the door to open far enough to let in the likes of Willie, Waylon, and the boys (and girls). I remain grateful to you, John.

After John brought The Driftwoods back to life a few years ago, we did a little thing with students at SUNY Oneonta learning how to mike up and record a live band. John picked Willie’s “Angel Flying Too Close To The Ground” and sang the hell out of it (not to mention a great Willie guitar solo).

You can give a listen to it here: https://www.facebook.com/thedriftwoodscountry/videos/2552835048184066/

My dad used to watch “Hee Haw.” Not religiously – that was for “The Lawrence Welk Show” – but often enough that I knew about Buck Owens and Roy Clark. My mother later revealed that Dad liked country music and was fond of Roger Miller (which explained how, at the age of four, I inherited the 45 of “I’ve Been A Long Time Leavin’,” a stone favorite to this day). “San Antonio Rose,” she said, was his favorite song.

The contradiction of “Hee Haw,” though, is that while it introduced an entire generation of obstinate northeasterners to country music, it also debased the genre via corny jokes and tired stereotype. Same goes for “Urban Cowboy” and the “Outlaw country” tag (that, as Waylon observed, done got outta hand) two decades later – they turned country music into some kind of aesthetic that distracted from brilliant and beautiful songs that deserve much closer attention.

All these years later, I’m still digging in. There’s so much. It’s so good.

Not only did John Thompson sing the hell out of "Angels Flying Too Close to the Ground" but every element of the Driftwoods rendition was clean, pure perfection!